The London Regional Children’s Museum has seen better days, but I have fond memories of going there as a kid. A highlight is when a traveling Jim Henson exhibit was set up there, and I got to see the actual muppets from my favourite movie at the time (okay, still), Labyrinth.

There’s a story about how one of the animatronic muppets from Labyrinth, Hoggle, was later neglected, misplaced, and eventually found in an airline’s unclaimed baggage department looking like this:

I feel like the entire Children’s Museum has followed a similar path as Hoggle. The building has been sold, but remains open while the owners figure out what to do with it, and when I visited recently, many of the exhibits were missing pieces or otherwise marred by age. In the room educating kids about outer space, a mysterious purple drawer has a sign reading “What’s in here?” It evokes my sense of childhood wonder—if they bothered putting a sign up, it must be something exciting and/or educational! What will I learn today?! I hastily yank the drawer open, only to find … nothing. It’s completely empty.

Perhaps a lesson about how vast and barren the vacuum of space is? Who knows.

Nearby, a dead astronaut hangs from the ceiling.

A tribute to David Bowie? Unlikely.

But the oddest area is the music room. It’s a large room, but like the empty drawer, it’s mostly dead space. There is no furniture—just instruments scattered across the floor. Most of them are fully or partially destroyed. Drums have tears across their leathery membranes, so that banging the splintered drumsticks against them sounds no different than banging them against anything else. A wooden contraption makes clicking sounds when I shake it, but it’s not any instrument I’ve encountered in this reality. There are children here, unsupervised, eyes vacant as they try to wrestle music out of the wreckage.

Where are their parents? Do they even have parents? Or have they always been here? Perhaps.

To distract myself from the racket, I look up, and this is what I see:

I recoil in fear from the kid in the middle, staring directly at me like I’ve interrupted … whatever he’s doing. But then I can’t tear my gaze from the stained glass window on the right. Can it be anything other than the wailing ghost of a dead child?

No. No. I’m a scientist, a man of reason—there must be some rational explanation for this. I turn to research for the cold comfort of knowledge, but unfortunately, there is nothing to put my mind at ease. It only gets stranger from here.

You Know, For Kids

The windows were created by Roy Edward Suhr, a local glazier, and installed in 1907 at Riverview Public School, which was later transformed into the Children’s Museum. (Source)

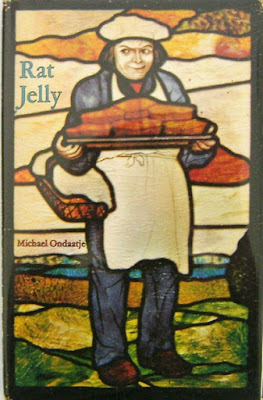

There were other windows, as well. Jack and Jill and The Big Bad Wolf lived at the school, but were removed for renovations, misplaced, then later found elsewhere. Sort of like Hoggle. Another one, The Pie Man, was used as the cover for a poetry book called Rat Jelly:

As has hopefully become clear, each window is based on an old nursery rhyme. The three still in the museum are Little Miss Muffet, Ride a Cockhorse to Banberry Cross, and Little Tommy Tucker.

Wait, cockhorse?

And who’s Tommy Tucker? Apparently he’s the dead kid on the right. The nursery rhyme goes like this:

Little Tom Tucker

Sings for his supper.

What shall we give him?

White bread and butter.

How shall he cut it

Without a knife?

How will he be married

Without a wife?

So I guess he’s singing for his supper, not educating kids about the wailing of the damned. And he’s given bread without a knife … and prematurely considering marriage. For some reason.

I wasn’t aware of Tommy Tucker, but he is big in pop culture, according to his Wikipedia page.

Wait, squirrel?

Tommy Tucker (Squirrel)

This is the squirrel named after the dead child at the Children’s Museum:

He, too, has his own Wikipedia page, because he falls into the (presumably small) category of famous cross-dressing squirrels.

Tommy Tucker (squirrel) toured the United States in the 1940s, wearing women’s fashions, doing tricks, and selling war bonds. He’s described as unusually docile, but did occasionally bite people, which makes me concerned about how often squirrels usually bite people.

After World War II, Tommy settled down and married another squirrel named Buzzy. But unfortunately, Tommy died in 1949. Whoever wrote the Wikipedia article seems to suspect foul play, saying he ostensibly died of a heart attack due to old age, then pointing out that squirrels usually live for more than ten years in captivity. Was it murder? Did Buzzy do it? Or did the spirit of Tommy Tucker appear to him in the dead of night, this time not wailing for his bread, but for the soul of the squirrel who stole his name?

The squirrel’s body was stuffed and mounted. He was passed along, and ended up in the possession of an old woman, who died in 2005. She thought Tommy should be in a museum, and bequeathed him to the Smithsonian. (Source)

The Smithsonian didn’t want him.

Now he’s encased in plexiglass inside a cardboard box in the office of that old woman’s lawyer. The glass case is there because moths were starting to eat away at him.

It appears that Tommy, like the other windows in the museum, like the museum itself, followed the path of Hoggle. He lived his life, then when the world couldn’t use him any more, he was forgotten, passed from person to person, eaten by wriggling things and the passage of time.

There’s always hope, though. After the startling discovery of Hoggle’s mangled muppet corpse, he was purchased by the Unclaimed Baggage Center, a museum/store in a small city in Alabama, and restored to, well, something vaguely resembling his former glory:

Everything dies, nothing lasts, but if you’re lucky, you’ll end up stuffed, preserved behind glass, scaring children in a museum. I find an odd sort of comfort in that.

This was originally posted on Medium: A Deep Exploration of the Terrifying Stained Glass Windows at a Run-Down Children’s Museum. I’ve started posting a few things there before I put them here, because I like what Medium is doing—basically paying content creators directly when subscribers like what they do. It’s a big improvement over the advertising-infected world of much of the rest of the web. Anyway, go follow me on Medium if you like that sort of thing.

Leave a comment